The Commodification of Pleasure

…and the enclosure of creative talent

Hello and congrats for reaching 2025, a nice rounded number and quarter century milestone.

On the 30th of January at 7pm I will be running an informal tech policy meetup in London with Ben Whitelaw from Everything in Moderation and Mark Scott from Digital Politics. If you’re in London around that time, you can register your interest here. More details to follow!

Perhaps you noticed that in December, the UK’s grand-high status quo maintainer Keir Starmer pledged to submit all creative works produced by this country to training datasets for AI: unless they opt-out, content produced by artists, musicians, and media publications, etc., will be automatically included in training data, and this action will not infringe on any copyright.

This makes sense. It isn’t good, but it makes sense. A key part of any industrial strategy these days is not just to undervalue labour, but to make it invisible. Look at the recent MAGA in-fighting: members of the US far-right are already bumping up against Elon Musk’s diseased compulsion to absorb workers into his parasitic corporate universe. The far right don’t like immigration and that’s it — but Elon Musk and other mangled business men do like it, as long as it brings “high end talent” into the US, so that they can “win” at whatever specific game they want to play this year.

Both of these debates represent a unapologetic hostility towards workers: that they should exist as droves of fungible individuals, waiting to become useful to a corporate machine or indeed an actual machine — like an AI model. When we instrumentalise creative talent like this, we enclose it behind ‘work’ and turn it into labour, which is a commodity. I think what often gets lost in conversations about work and labour is pleasure: we can define pleasure as something distinct and separate from work, but also as something that co-mingles with work, and is even borne out of work.

There is pleasure in making. I take pleasure in writing these words and always feel a bit shit about using an opaque online platform to facilitate their delivery to you. I enjoy making all kinds of weird things in my spare time (like these games) that are probably impossible to sell, and that I wouldn’t want to sell anyway. I am incredibly privileged in that I have the time to make stuff that’s just for me, and I would never try to monetise any of this because the pleasure of making would transform into a pressure to produce. As many creators out there will know, the pressure to produce is kind of haunting; there’s a strange driving compulsion to stuff your hobbies and creative outlets into a work-shaped hole.

In Bullshit Jobs David Graeber theorised that work which gives pleasure and fulfilment — such as being an artist, care-giving, or being a teacher — traditionally receives less financial compensation, because the market assumes the pleasure and fulfilment is somehow ‘enough’, and it would be in poor taste to try ascribe value to this work in money; the value is unquantifiable and felt within each individual who takes pleasure in doing the work. Looking after children and making art is its own reward. But profit is earned from this work, just not by those who are doing it: when art and media is refactored into training data, it’s for the continued improvement of AI models and the expansion of wealth of a few individuals. It’s not just the labour that is commodified, but also the pleasure in making.

I’m discussing this now because I think that pleasure is increasingly hard to find in a world that is mediated by digital systems. The portals to our cultural universe are collapsing (or arguably have already collapsed) into one single rectangular window (a ‘phone’!). There is a built-up residue of digital services which continuously try to replace the theatre, the cinema, the library, and traditional news outlets. These services drip-feed, paywall, and ration our pleasure. Or, as L. M. Sacasas put it recently, they delegate it. In fact while I was writing this piece, Mark Zuckerberg announced an end to third-party fact checking on his platforms. This is a move that will undoubtedly make the platforms worse to experience as a passive consumer and harder to use for someone who relies on them for income — literally reducing the pleasure in both work and leisure.

The drudgery of work and boring life admin forces us to seek out pleasure in tedious pockets: When I take the train I use that time to listen to podcasts or read; I am overlaying pleasure activities onto the ungodly chore of commuter travel. The pleasure of reading/listening doesn’t exist for its own sake; I’m using it in 20-minute intervals to distract me from the repetitive grind of capitalist living. When you go on holiday, you have to tolerate the experience of an airport (e.g. a labyrinth of waiting rooms where you are a captive audience for luxury brands), and then sit in a flying tube where you share recycled air with strangers. The holiday itself is a thing you do to temporarily ease the every day stresses of life; it’s not restorative or transformative, it just brings you back to an acceptable operating level.

When pleasure is mediated in this way, it’s hard to really remember what it even looks like. Can you really class scrolling through social media as a pleasure activity? Aren’t you only doing it because it’s so frictionless and it feels like there’s nothing else? Let’s come at this from another angle: Broad City is a show about the misadventures of two women living in New York in their mid-20s, but unlike the show Girls it actually exhibits some cultural awareness. In Broad City, one of the main characters, Ilana, is a throbbing main artery for pleasure. She views her day job as a negligible symptom of being alive, and uses her office as a space to sleep in, or just somewhere to wait before her next sexual encounter. She wears her pursuit for pleasure proudly, like a loud colourful snowsuit. Someday I hope to be just like her. Anyway, in the months following the 2016 presidential election, Ilana was completely unable to achieve orgasm. The juicy apex of her main pleasure apparatus was dehydrated to a desensitised husk because she was too distracted by the horrifying state of her political climate.

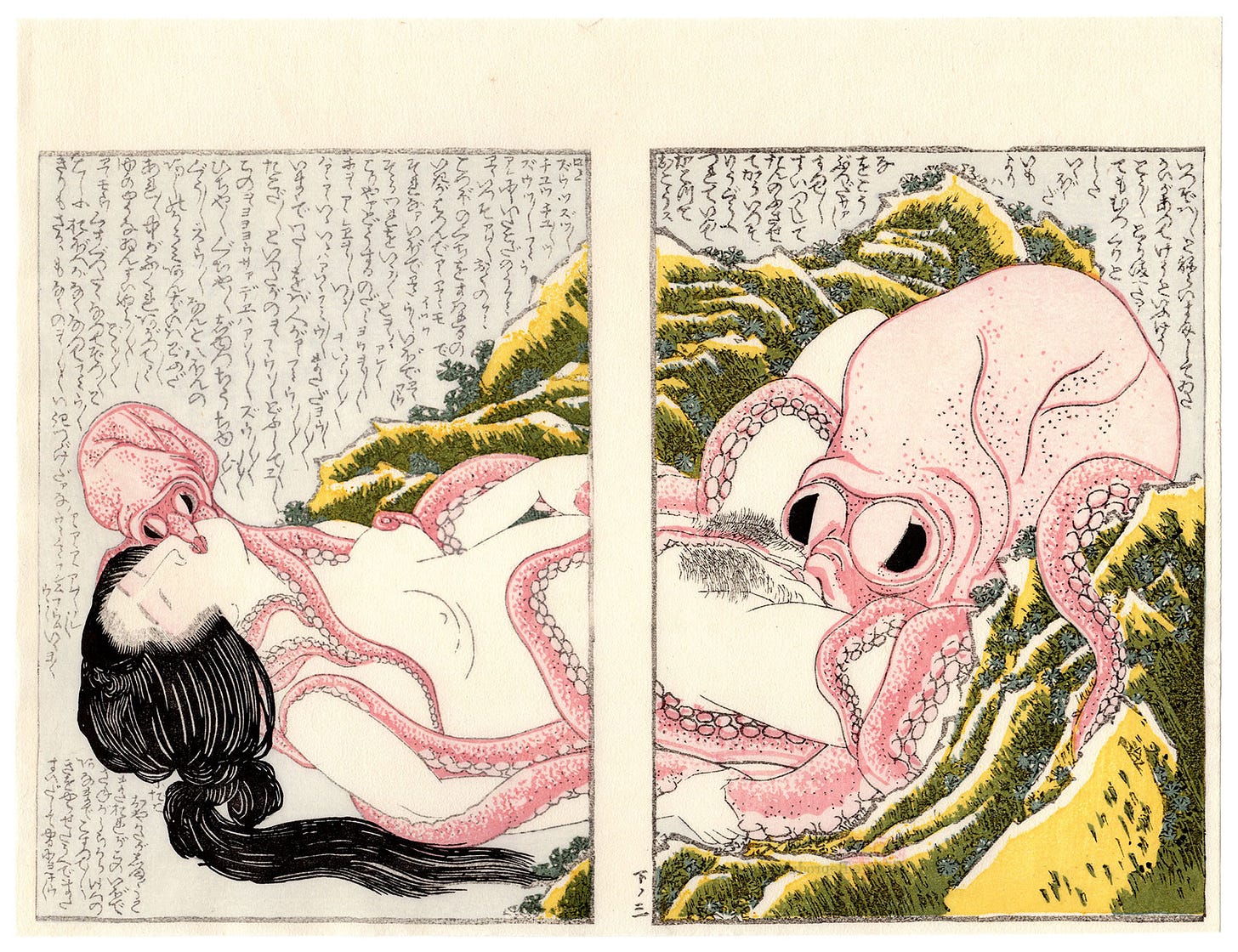

Do you see? Please tell me you see. When pleasure is enclosed and commodified, it becomes harder to know what it actually is — and therefore how to access it. The transformation of creative output into labour dulls the pleasure of making. The flattening of cultural experiences into frictionless micro-holidays from reality can sometimes make us forget that there are other ways to enjoy ourselves. I struggle with taking pleasure from self-improvement or setting work-based goals or anything like that, so when people ask me if I have any resolutions for the new year I just say ‘have more sex’ — and that is what I plan to do. I’m diving head first into hedonism this year. What pleasure will you seek in 2025?